Industrial Policy: Is It the Perfect Enemy of the Good?

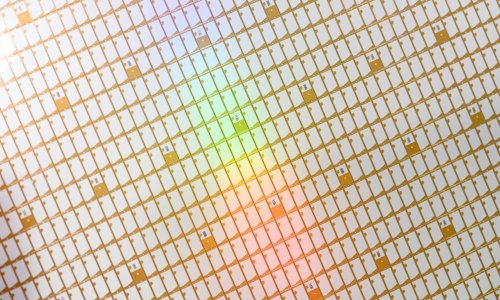

Photo: JENS SCHLUETER/AFP/Getty Images

There has been a lot of activity recently on the trade front—farmers demanding more market access negotiations, a House committee voting to ban TikTok, the publication of the administration’s 2023 Trade Policy Agenda—but on those I am going to follow the advice we all got from our mothers: if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything.

Instead, I want to comment on something else that came out last week—the Department of Commerce’s guidance on applying for the federal funds made available through the CHIPS and Science Act. This guidance has been eagerly awaited, notwithstanding Secretary Gina Raimondo’s warnings that there is no free lunch when it comes to government money and that applicants should expect strings to be attached. It turns out she was right about that. The strings come in three categories.

The first is not a string but a welcome announcement—the government will not only make grants but will consider loans and loan guarantees as well. This is a smart move because it will enable the government to provide more funding and therefore expand the scope of the program.

Second, there are a variety of widely anticipated national security restrictions. For example, fund recipients must commit not to build factories in China or invest or transfer technology there. In some cases, these conditions simply repeat existing restrictions on transfer of critical technology to China, and companies are already familiar with them. Others, such as factory construction restrictions, were clear from the beginning and come as no surprise. Plus, given the current state of the bilateral relationship, it is unlikely high-tech companies are making such plans anyway.

Third and most problematic, are a variety of what might best be called social policy or economic restrictions. The one that has gotten the most ink is the requirement to stand up childcare programs for workers in the new plants, but there are workforce development and assistance provisions as well, along with requirements for union labor to be used in facility construction. On the economic side, restrictions on increased dividends and stock buybacks, as well as potential profit-sharing with the government have raised some eyebrows.

In my view, these are good things that companies should be doing anyway, although the burden will fall unequally depending on a company’s size. A large manufacturer with a substantial existing workforce probably has these social programs in place already and can fairly easily expand them to new facilities, but small- and medium-sized enterprises will face more of a challenge.

The larger philosophical question is whether this is yet another example of the perfect being the enemy of the good and a kind of social and economic mission creep. The goal of the legislation is to revitalize the U.S. semiconductor industry and increase its domestic manufacturing capabilities. Preoccupation with doing that the “right” way may result in fewer applications for the funds, particularly from smaller companies with more innovative approaches, which would make the program’s production goals more difficult to attain. Meeting these requirements will also add to project costs, which in the end usually means higher prices and less competitive products.

The government’s response, of course, will be “my money, my rules,” and the administration will not be wrong about that, although technically it is the taxpayer’s money not the government’s. Companies can always opt not to apply if they find the conditions objectionable or onerous. (Even if they support the goals of the conditions, they may conclude that the compliance burden of paperwork and inspections may be too much for them to handle.)

The danger is that if enough companies decide not to apply for the funds, the program’s goals may not be attained, or, as mentioned above, innovative ideas may fall by the wayside. On the other hand, the potential financial reward for participating is so large that many companies may swallow any reservations and forge ahead.

If they do, it will be a double win for the administration—the revitalization of a critical industry done in a way that benefits the workers (and their children) and ensures the rewards do not accrue exclusively to the shareholders and corporate executives. That would give meaning to the administration’s oft-expressed desire to pursue worker-friendly policies—remember a trade policy for the workers? It is also a useful reminder that, for the most part, it is domestic economic and social policy that redistributes benefits, not trade policy.

There is always a tipping point for these programs where the juice is not worth the squeeze. It is not yet clear in the case of the Commerce Department’s CHIPS guidance whether that point will be reached. I hope that point does not arrive, and the program ends up succeeding in its primary objective by doing it the “right” way. At the same time, I hope the administration will have the good sense to redesign the program if it turns out not to work as intended.

William Reinsch holds the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.