Vaccine Confidence & National Security in the Covid-19 Crisis

Report by Katherine E. Bliss, Heidi J. Larson, and J. Stephen Morrison

In July 2020, the CSIS Global Health Policy Center and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine’s Vaccine Confidence Project™ convened a bipartisan international panel of experts to assess the implications of misinformation and vaccine confidence for U.S. national security.

As the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic unfolds, the United States has entered a new phase of heightened hope in the race to control the outbreak and get ahead of evolving variants. The U.S. government and health sector share an imperative to move quickly to immunize at scale and to address disparities in vaccine access at home and abroad.

Doctor John Rajiv writes a note before receiving his first dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine in December 2020.

| JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP via Getty Images

But public trust and confidence in vaccines, science, and public health authorities are both fragile and absolutely pivotal. What is at stake is fundamentally a matter of national security: achieving herd immunity that truly and rapidly restabilizes public health, economic vitality, and society at large.

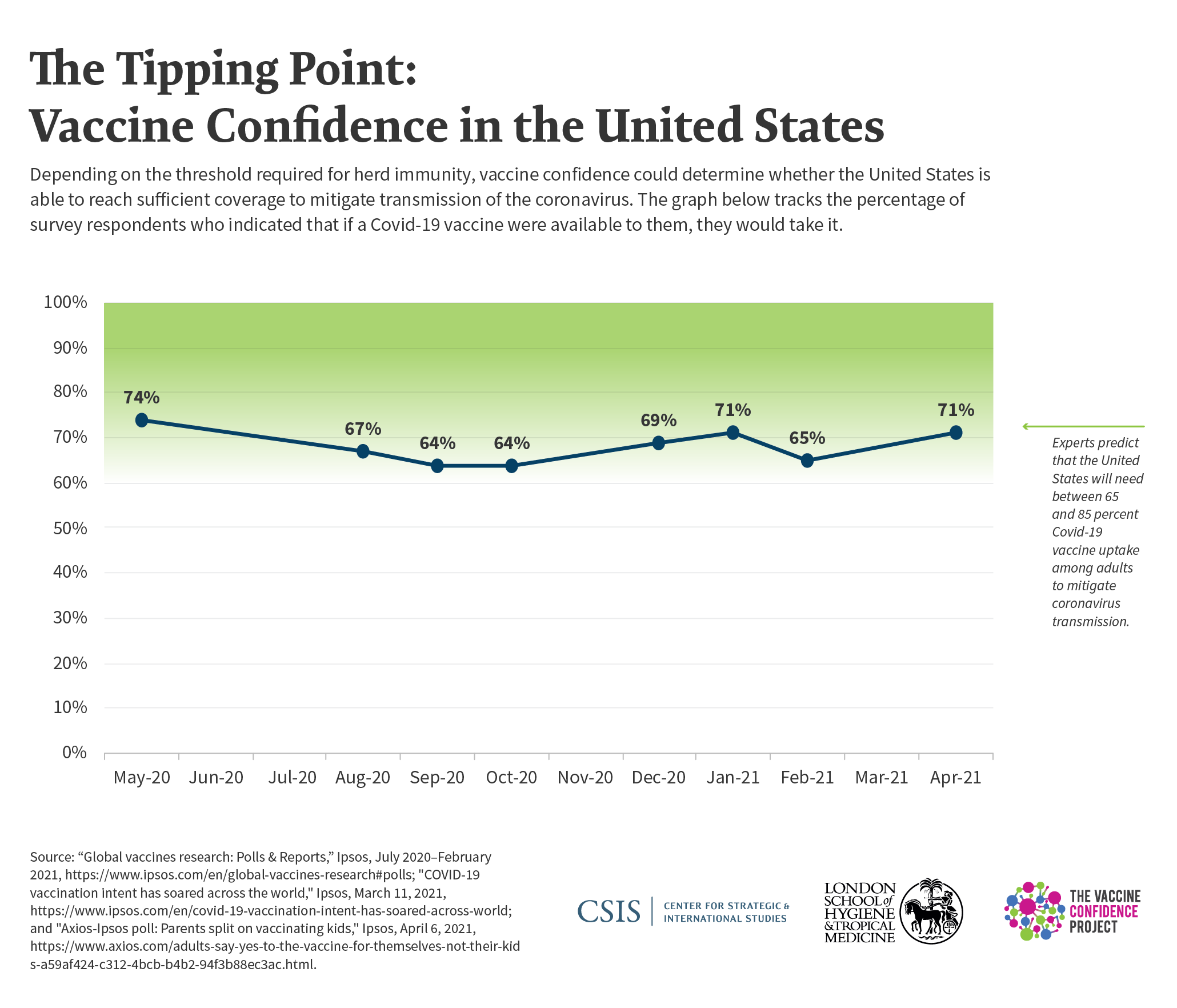

In the race to achieving herd immunity for Covid-19, finding new ways to address the challenge of vaccine hesitancy has never been more important.

A Crisis Decades in the Making

Vaccine hesitancy is not exclusive to the Covid-19 pandemic, nor is it confined to the United States. It has been globalizing over many years and accelerating in recent decades.

Concerns about immunizations initially surfaced soon after the first smallpox vaccines were introduced in the eighteenth century. Opponents either minimized the threat posed by smallpox or warned that the vaccines would cause other health problems. These issues resurfaced in the early-twentieth century and intensified as global immunization programs expanded. With the advent of the internet and other digital technologies in the mid-1990s, vaccine hesitancy grew even more.

Vaccine hesitancy today is highly context-specific. Where vaccine-preventable diseases are no longer common, people can become complacent and question the need for vaccines. Vaccine mandates can also trigger opposition by parents, who may try to reject state, school, or sport district vaccination mandates. Parents may also question or have concerns about the sheer number of vaccines required for young children.

There is also fertile ground for vaccine hesitancy in the historic neglect and abuse of minority populations by health authorities. Examples range from the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments on Black men begun in the 1930s to deliberate sterilizations of Mexican-American women in California in the 1970s.

But while vaccine hesitancy may manifest in context-specific ways, there are common overarching themes that drive it.

Some people view the scientific language around vaccines as elitist and inaccessible, believing that it may conceal true safety risks. Another set of concerns centers around the political or economic motives of vaccine developers and manufacturers.

A third narrative motivating vaccine hesitancy emphasizes personal liberties and choice. For some populations, vaccine hesitancy is tied to conspiracy theories and political movements that broadly reject government law enforcement or regulatory authority.

This viewpoint has strong religious components, with some adherents rejecting government science because they see it as undermining a Christian nationalist outlook.

While people may feel hesitant about vaccines for different reasons, the reality is that there is considerable overlap among diverse perspectives.

Vaccine Hesitancy within the Covid-19 Crisis

When it comes to Covid-19, vaccine fears were already present before the Trump administration launched Operation Warp Speed to stimulate vaccine research and the development of a Covid-19 vaccine. Even the language of “warp speed,” however, wound up amplifying concerns about Covid-19 vaccines being developed too quickly and increased vaccine hesitancy.

Logistical challenges have also amplified vaccine uptake issues. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has allocated shipments of vaccines to states, territories, tribal areas, and major urban centers, leaving distribution planning largely up to local governing bodies in those entities. The considerable variation in local planning processes, distribution capacities, and responsiveness to community needs has shaped the rollout of vaccines across the country.

A man sleeps in the post-vaccination observation area after receiving his Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccination at Wayside Christian Mission on March 15, 2021, in Louisville, Kentucky.

| Jon Cherry/Getty Images

Possibly because of this, early vaccine distribution data shows that whites within eligible recipient groups have secured a disproportionately high percentage of available doses. And yet in communities across the country, the percentage of positive tests in minority communities has been routinely higher than in majority white neighborhoods in the same areas.

Setting up vaccination hubs in centralized locations may help reach many more people, including minority groups or those who are more hesitant about vaccines. However, differential access to online registration services or availability to wait at mass vaccination sites during workday hours may account for some of the racial disparities in access to Covid-19 vaccines. Offering vaccines in spaces beyond health clinics and making appointments available to people outside of working hours will reach some who face challenges in getting to facilities during conventional hours of operation.

People wait in line in Immokalee, Florida for services from the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and Partners in Health to test, educate and vaccinate the poverty-stricken community during the Covid-19 outbreak.

| Spencer Platt/Getty Images

But making vaccines accessible is only part of the equation. Going door to door, talking with household decisionmakers, and answering their questions is also important.

The questions that need to be addressed vary by community and demographic. For example, the legacy of neglect or abuse by health authorities contributes to vaccine hesitancy among some Black and Latino populations. These communities have also expressed concerns about the experimental nature of Covid-19 vaccines.

But regional and political differences are also at play in vaccine hesitancy. Recent surveys show that 44 percent of Republicans do not intend to get a Covid-19 vaccine, compared to 18 percent of Democrats. This could reflect the comparatively lower impact of Covid-19 in some rural communities, where residents are more likely to identify as Republican. Some groups may reject the vaccines because of perceptions of self-sufficiency or because they philosophically object to large government programs.

At least 70 percent of people in the United States will need to be immunized against Covid-19 in order to reach herd immunity and move toward national recovery from the pandemic. Until each group is addressed on its own terms and in its own unique context, vaccine hesitancy will continue to pose a challenge to achieving this goal.

Health & Community within the Information Revolution

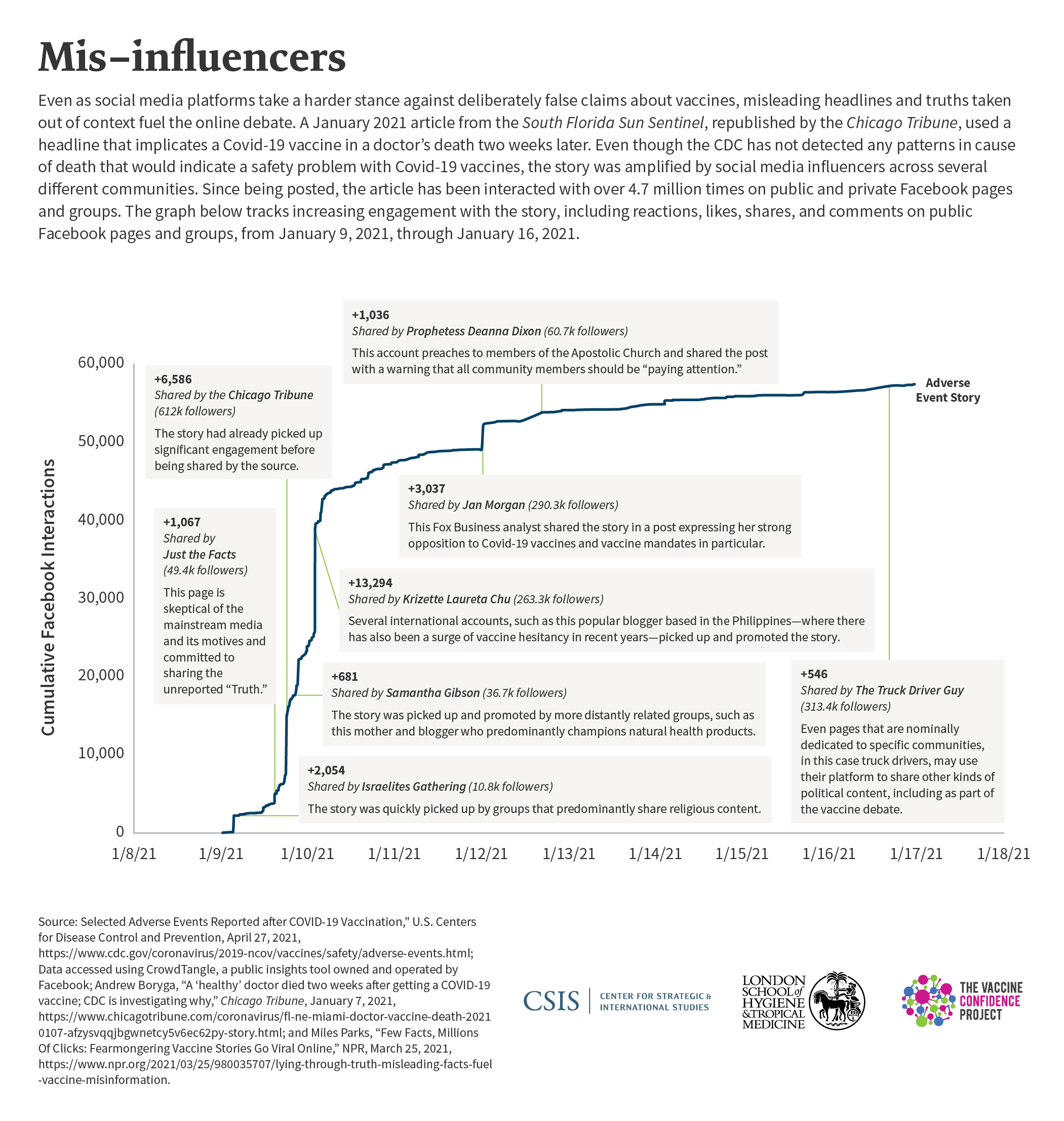

The spread of misinformation, through face-to-face conversations, as well as through mainstream and digital media, is also playing a significant role in undermining confidence in vaccines.

The role of new digital communications in amplifying the spread of misinformation about coronavirus vaccines has been central to debates about vaccine confidence in the Covid-19 context. The ability to reach hundreds of thousands of followers quickly with just a click of a mouse makes controlling the transmission of false information uniquely challenging, particularly when it is disseminated through a complex network of contacts.

Extremist groups, including anti-vaccination groups, have used social media to spread misinformation and to organize protests or otherwise disrupt vaccination programs. For example, well before the first Covid-19 vaccines had even entered phase III clinical trials, an online film, "Plandemic", spread misinformation regarding the motives of the companies developing them and the intentions of government scientists. Featuring a former researcher who claimed her warnings about vaccines had been suppressed by top government experts, the video was first posted to Facebook on May 4, 2020. Within a week, it had been shared thousands of times and had accrued 8 million views on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram. The film has been taken down, but many of its original claims continue to circulate on the internet.

Whether users or subscribers have a right to use a private service such as Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, WhatsApp, Snapchat, or YouTube to sow doubt or disseminate false information has become a highly debated, vexing question. Managing posts that merely pose concerns or share perspectives has also become controversial and raises ethical dilemmas about who gets to determine which posts constitute false information, as opposed to questions or uncertainty, about Covid-19 vaccines.

Recognizing that their platforms have been used to spread misinformation, sometimes inadvertently, and sometimes deliberately, companies including YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook have taken steps to both censor or suppress malign content and amplify public health content. Even so, there is no clear consensus among social media companies on how to proceed.

Vaccines for Health Security & National Security

It is no surprise that the pandemic response is a U.S. national security priority. The corrosive economic impacts of the pandemic continue to worsen, despite stimulus packages, payroll protection plans, and other actions taken at the federal, state, and community levels to prevent evictions and keep commercial interests afloat.

Early actions taken by the Biden administration signal that controlling the pandemic is a top national security priority for the White House. These high-profile actions include the president’s first National Security Memorandum, the publication of a 200-page national strategy, and the commitment of up to $3 billion to vaccine confidence-building activities.

President Joe Biden tours the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland in February 2021, flanked by (from R) Dr. Kizzmekia S. Corbett, Dr. Francis Collins, White House COVID Coordinator Jeffrey Zients, White House Chief Medical Adviser on Covid-19 Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Barney S. Graham.

| SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

However, despite signs that the labor market is starting to recover from the economic impacts of the pandemic last spring, U.S. competitiveness remains mixed. In 2020, China overtook the United States as the principal destination for foreign investment. The United States’ poor performance in addressing the pandemic has also exacerbated the trend of declining enrollment of foreign students and slowed the recruitment of foreign workers to the high-tech sector. With many schools and universities remaining in a hybrid or distance-learning mode, U.S. research and development competitiveness could also drop.

Social media technology has enabled propaganda networks intent on undermining U.S. global influence to raise questions about the motives of the U.S. government in distributing vaccines. Such posts enable them to undermine the influence of the United States abroad while amplifying praise about vaccines produced in Russia or China.

Issues have also arisen about confidence in Covid-19 vaccines among members of the U.S. military, which could have detrimental effects on national security. U.S. servicemembers have a complicated history with vaccine confidence dating back to late 1990s when the Department of Defense began requiring troops to be immunized against infection with anthrax, citing the potential for adversaries to deploy anthrax as a biological weapon. But reports of adverse reactions fueled mistrust, and the circulation of digital posts arguing that the Pentagon downplayed servicemembers’ concerns may be contributing to hesitancy in the current context.

Providing clear and accurate information to promote understanding among servicemembers can help achieve a high rate of Covid-19 vaccination among military communities. This will help enhance operational readiness and promote the health and well-being of the members of the military and their families, who play influential roles within their communities, whether in the United States or on military bases abroad.

Bolstering Confidence Now & Preparing for the Future

With the successful development and distribution of new vaccines, there is hope in the United States that the acute phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic may soon come to a close. As of May 3, 2021, more than 104 million people in the United States have been fully vaccinated, and more than 147 million have had their first doses of Covid-19 vaccine.

Social media platforms have made public commitments to remove, inform, and reduce misleading content and to bring these efforts to scale. At the same time, the U.S. government and its allies have become more aggressive in tracking and countering Russian and Chinese online disinformation campaigns aiming to undermine confidence in Western vaccines.

Nevertheless, public confidence and trust—in vaccines, authorities, and science—continue to fall significantly short of what is required to exit the pandemic crisis.

To move the United States forward in vaccine confidence and support its external partners, the CSIS-LSHTM High-Level Panel recommends bolstering efforts in five critical areas:

1. Innovations in reaching diverse and underserved populations with vaccines delivered in the context of health and social services.

The Biden administration has called for the public sector at the national, state, and local levels to take the lead in strategic engagement of the populations that experience the greatest disparities in the face of Covid-19 and that harbor the greatest skepticism about vaccines.

Vaccines should be delivered along with other health and social services that address the negative economic impacts that have left millions unemployed and unable to afford housing, food, and other necessities. Enlisting trusted community leaders will be essential in advancing such efforts.

2. Pledges and actions by mainstream and digital media platforms to stop the spread of misinformation and to collaborate with health providers and the scientific community to increase the availability of accurate content.

The High-Level Panel recommends that the leadership of U.S. mainstream media outlets, in alliance with digital media platforms, build upon the recent advances in content moderation and lay down common principles of transparency and accountability, establish shared standards and definitions, and spotlight best practices and lessons learned.

Social media platforms can effectively mitigate the presence of harmful content and alter algorithms to prevent the automatic spread and reinforcement of misinformation and disinformation (e.g., “filter bubbles”) as well as develop and optimize other automatic processes to amplify and disseminate accurate information.

3. Increased engagement by key social and economic sectors to empower people to make informed choices about Covid-19 vaccines.

The Biden administration has recently forged new partnerships with leadership of critical social and economic sectors, such as transportation, education, and agriculture, urging them to step forward and speak. Those who have the most to gain by a successful Covid-19 vaccine introduction—and the most to lose if that effort fails—have committed to engage their respective communities in a sustained dialogue about vaccines’ merits and risks.

Iconic cultural figures with substantial media presence and bipartisan reach can also be highly impactful in supporting dialogue and disseminating messages to a broad audience. Far more conversation is warranted among educational institutions, businesses, healthcare providers, the agricultural sector, and the security, law enforcement, and military communities.

4. Greater executive branch coordination and action beyond the emergency.

The White House has established a powerful Covid-19 Response Team, recently re-established a National Security Council (NSC) directorate for global health security and biodefense, and launched an Equity Task Force. It has elevated the head of the White House Office of Science and Technology to cabinet rank.

These entities, along with the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and State and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, in collaboration with the Domestic Policy Council, can contribute to a coordinated U.S. policy formulation that prioritizes addressing misinformation and determines the most effective strategies for bolstering vaccine confidence.

5. Increased U.S. support for global immunization partners.

As the Department of State and White House, joined by other departments and agencies, develop a global health security strategy and define U.S. diplomatic priorities, they should elevate efforts to strengthen public confidence in vaccines, public health, and science globally.

Washington should use its influence to shape a coordinated international approach to the shared concerns of vaccine confidence and misinformation. The case that vaccine confidence and misinformation are matters of global security should be systematically incorporated into high-level dialogues at the UN Security Council, the G-7 and G-20, the Quad (United States, India, Japan, and Australia), and the renewed U.S.-European transatlantic relationship.

The recent United States commitment of $4 billion to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to support the COVAX Facility’s effort to deliver 2 billion doses to 20 percent or more of the populations of 92 lower- and lower-middle-income countries over the next two years, can be leveraged to encourage other donors to reinforce their support for the initiative.

Conclusion

In the space of a year, the Covid-19 outbreak has sharpened the argument that pandemic preparedness and response, including the distribution of vaccines, are matters of U.S. national security. Until the pandemic is effectively controlled, neither the economy nor society can reopen safely and effectively.

Several effective vaccines are now publicly available. But with variants of Covid-19 proliferating, there is still more to be done. Strengthening vaccine confidence, shaping the information environment, and bringing trusted, reliable science to skeptical and anxious publics can protect health security and national security now and in the future.

For a complete list of recommendations, read our report Why Vaccine Confidence Matters to National Security.

A doctor holds a patient's hand in the Covid-19 alternative care site, built into a parking garage, at Renown Regional Medical Center on December 16, 2020 in Reno, Nevada.

| Patrick T. Fallon / AFP via Getty Images

About the Authors

Katherine E. Bliss

Senior Fellow, Global Health Policy Center

Katherine E. Bliss brings her expertise in the social sciences, Latin American studies, and international relations to her work analyzing U.S. government support for health programs in low- and middle-income countries. She is particularly interested in how political and cultural perspectives shape approaches to such global health challenges as HIV/AIDS; vaccine-preventable diseases; and access to safe drinking water and sanitation. Trained as a historian, Katherine spent the early part of her career teaching at the university level and publishing books and articles on gender relations and public health in twentieth-century Mexico. A Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellowship enabled her to shift her focus to global health policy, placing her at the U.S. Department of State, where she worked on environmental health issues and the development of foreign policy approaches to pandemic preparedness. At CSIS, Katherine has previously served as deputy director and senior fellow within both the Americas Program and Global Health Policy Center, where she oversaw a multi-program project on the influence of the BRICS countries on the global health agenda and directed the Project on Global Water Policy. Her recent work has examined the health situation in the context of the Venezuelan political crisis and the challenges facing immunization programs within fragile or disordered settings. Katherine received her A.B. in history and literature, magna cum laude, from Harvard College and her Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago. She completed a David E. Bell Fellowship at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies.

Heidi J. Larson

Founding Director, Vaccine Confidence Project™, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Senior Associate (Non-resident), CSIS Global Health Policy Center

Dr. Heidi J. Larson is an anthropologist and director of The Vaccine Confidence Project™; professor of anthropology, risk, and decision science, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; clinical professor, Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington; guest professor at the University of Antwerp, Belgium; and a former fellow at the Chatham House Centre on Global Health Security.

J. Stephen Morrison

Senior Vice President and Director, Global Health Policy Center

J. Stephen Morrison is senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and director of its Global Health Policy Center. Dr. Morrison writes widely, has directed several high-level commissions, and is a frequent commentator on U.S. foreign policy, global health, Africa, and foreign assistance. He served in the Clinton administration, as committee staff in the House of Representatives, and taught for 12 years at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He holds a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Wisconsin and is a magna cum laude graduate of Yale College.

The authors thank the members of the CSIS-LSHTM High-Level Panel on Vaccine Confidence and Misinformation for their insights and contributions to the report and its recommendations. For the full list of panelists, see the full report: Why Vaccine Confidence Matters to National Security.

The authors would also like to thank:

- Michaela Simoneau, Program Manager, CSIS Global Health Policy Center

- Sarah Grace, Producer & Multimedia Content Lead, CSIS iDeas Lab

- William Taylor, Designer, CSIS iDeas Lab

- Jacqueline Schrag, Lead Developer and Digital Projects Manager, CSIS iDeas Lab

- Jonathan Choi, Web Developer Assistant, CSIS iDeas Lab

- José Romero, Web Development Intern, iDeas Lab, CSIS

- Laurel Weibezahn, Multimedia Producer, CSIS iDeas Lab

- Liz Pulver, Junior Multimedia Producer, CSIS iDeas Lab

- Jeeah Jehanne Lee, Senior Publications Manager, External Relations

- Ali Corwin, Director, External Relations

- Ben Connors, Director and Andreas C. Dracopoulos Chair in Innovation and Creativity, CSIS iDeas Lab

The panel’s work is supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.

A product of the Andreas C. Dracopoulos iDeas Lab, the in-house digital, multimedia, and design agency at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.