Congress on China: Then and Now

Photo: NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics > Trustee China Hand

By Scott Kennedy

With the Senate voting on June 8, 2021, to adopt the United States Innovation and Competitiveness Act by a vote of 68 to 32, it is safe to say that this is the most comprehensive action by Congress on China policy EVER.

The House of Representatives still has to consider the legislation, and it is likely that the contours of a final product will be changed. Nevertheless, this is a historic moment for two reasons: the scope of the legislation and the contrast with the last major congressional action on China just over 20 years ago when China was on the edge of entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The Senate’s bill is not a singular strategic initiative designed and authored by a single legislator or within a single committee; instead, it pulls together multiple pieces of legislation and ideas from a large number of senators on different committees. Many of these elements were originally introduced last year in the wake of the pandemic, which led to a large leap in introduced bills, only a few of which made it over the finish line in 2020.

Although pieced together—and still unfinished—the bill adds up to a coherent strategic statement on China policy. It includes a vision of the nature of the relationship—a strategic competition framed in ideological terms, between free-market democracies and a state-capitalist autocracy. It puts forth broad policy goals on a wide range of issues and with respect to every part of the globe, from sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East to the Arctic. There is substantial attention to strengthening U.S. defenses on economic issues, dual-use technologies, and cyber. And, most prominently, it commits a historic level of spending—over $250 billion—for research and development (R&D), advanced manufacturing, and improving supply-chain resilience.

One can take issue with individual details and even some of the larger initiatives. There needs to be more vigorous debate about how much Congress should appropriate for these efforts, how to raise the likelihood investments yield valuable benefits for the United States as a whole, what type of supply chain adjustments are genuinely necessary and not create new kinds of vulnerabilities, and how the different elements will work in harmony with each other. Nevertheless, this congressional effort on China is without a doubt unprecedented in scale and scope.

There have been two other big moments when Congress weighed in on China policy in a major way that had a substantial effect on the substance and direction of U.S. policy. In April 1979, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act, providing a greater legal foundation than executive branch actions for unofficial U.S.-Taiwan relations, including U.S. military support. And in 2000, Congress voted to give China permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status. The House voted in May 2000, 237-197; and the Senate followed in September 2000, approving 83-15. Although often portrayed as a vote approving China’s entry into the WTO, in actuality, the vote was merely about whether the United States and China would continue to enjoy most-favored-nation (MFN) tariff treatment toward each other in the wake of China’s WTO accession (which occurred on December 11, 2001). The decision on China’s entry had been decided through negotiations over its accession protocol with individual WTO members, with the U.S.-China negotiations concluded in late 1999. Nevertheless, Congress’s endorsement of PNTR put a foundation under U.S.-China commercial relations and ushered in a period in which U.S. policy was centered around the goal of integrating China into the international system.

Although major actions, they still would pale in comparison to the Innovation and Competitiveness Act, should it become law.

What also comes through from the new measure is how Congress’s view of China has fundamentally flipped. This is not news for anyone with a pulse, but this bill and the votes put a fine point on it. This bill reconfirms the fact that the United States has abandoned a strategy of facilitating China’s integration into the international system with the expectation that such efforts would result in a more open, market-oriented Chinese economy, a more liberal political environment, and less aggressive activity internationally. There is an unsettled debate about whether the strategy was ever valuable or was ill-fated from the outset—my own view is that the United States and the world have benefitted immensely economically and strategically—but it is clear that, at a minimum, unconditional engagement is outdated and the United States needs a new approach which seeks China’s integration but is prepared for other outcomes. It needs to place much greater conditionality on the relationship and shift its attention to self-strengthening at home and coordination with other like-minded countries, a transition Congress is trying to facilitate.

This entirely understandable reorientation comes through loud and clear in a comparison of the Senate’s votes. Thirteen senators who cast a vote on June 8, 2021, also cast a vote on the PNTR on September 19, 2000. As Figure 1 shows, 11 of them voted “yea” both times, granting PNTR and then supporting building the United States’ tools to compete against China. The two exceptions are consistent with the broader change, as Senators Inhofe and Shelby voted “nay” because the final package left out their amendment requiring that defense spending rise as much as non-defense discretionary spending.

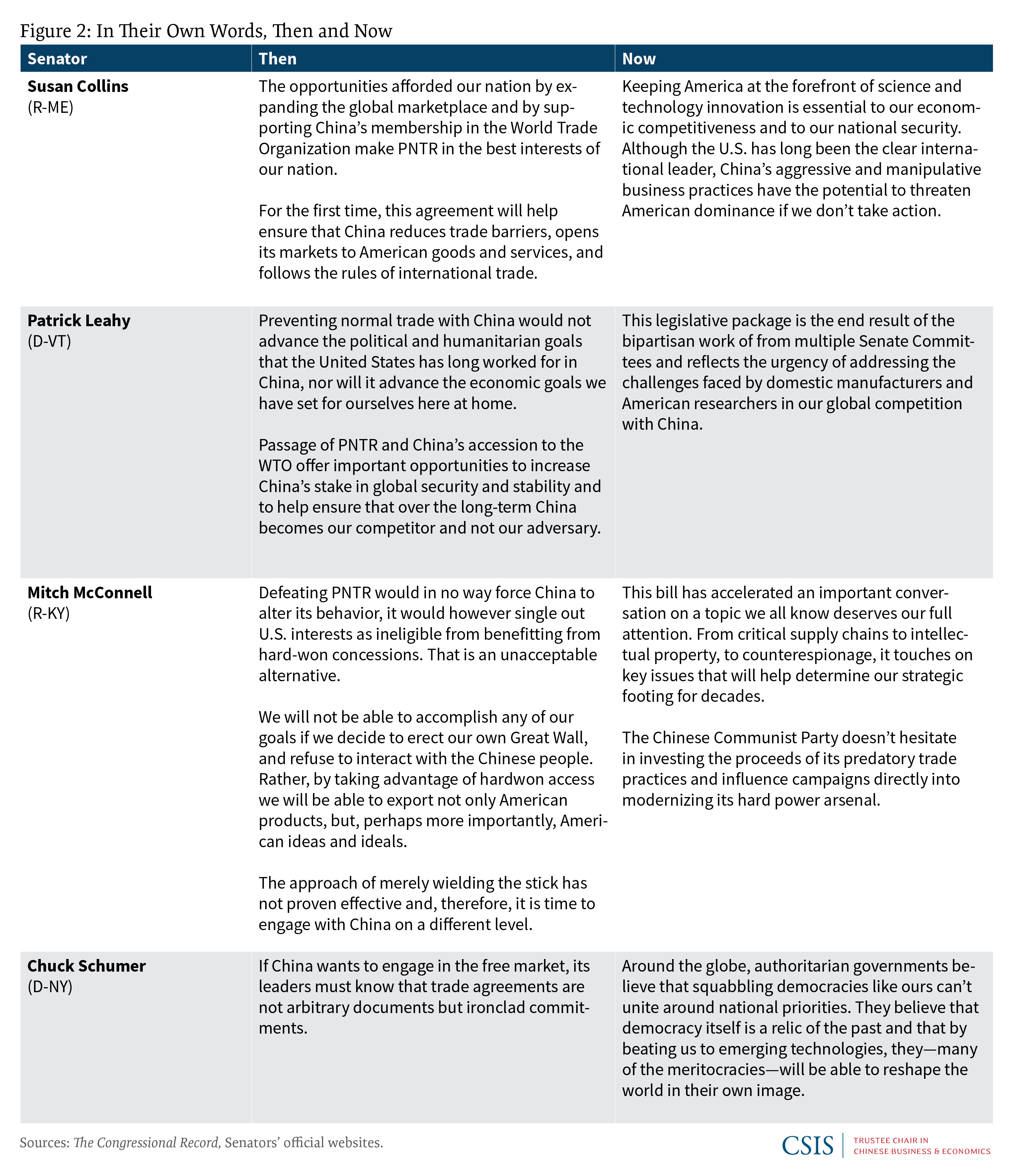

In addition to comparing senators’ votes, the change in expectations is also visible by comparing how they defended their positions (see Figure 2). What comes through is the conditional, non-absolutist tone of their language. Senators shifted from being more hopeful to being far more concerned; yet at the same time, at both moments, their views are nuanced and probabilistic. Contra the impression given by James Mann in his book, China Fantasy, in September 2000, senators who voted in support of PNTR were not driven by naïve idealism. Instead, they thought that on balance granting PNTR would achieve more than not doing so. Moreover, they emphasized that PNTR (and WTO entry) only raised the possibility of improving Chinese behavior but did not guarantee it. Conversely, in this month’s vote, although far more skeptical, the language is about a long-term competition with China as opposed to war with an enemy. Congress has taken a hawkish turn, but it is still pursuing a multifaceted approach that does not foreclose the possibility that U.S.-China relations could eventually be stabilized and not devolve into violent conflict.

Not only is it possible that the House of Representatives will come forth with a bill that is far from identical, but it is also entirely conceivable that partisanship will intervene and the initiative will come to naught. But if a final bill does emerge from Congress, it will be sent to the desk of an individual who himself 21 years ago cast a “yea” vote on PNTR, using language similar to those of his fellow senators.

Granting China PNTR and bringing China into the global trading regime continues a process of careful engagement designed to encourage China’s development as a productive, responsible member of the world community. It is a process which has no guarantees, but which is far superior to the alternatives available to us.

And just like them, President Biden’s views on China have evolved substantially; his administration has been clear that China is a strategic competitor and as his recent executive order on connected software applications states, is, in fact, an adversary. Hence, it is virtually guaranteed that despite Senator Biden’s vote 21 years ago, a President Biden would sign whatever bill reaches him eventually. Times have changed, fundamentally.

Scott Kennedy is Senior Adviser and Trustee Chair in Chinese Business & Economics at CSIS.

Related Trustee Chair Activity

Commentary: Scott Kennedy, “A Complex Inheritance: Transitioning to a New Approach on China,” January 19, 2021.

Microsite: Mapping the Future of U.S. China Policy: Views of U.S. Thought Leaders, The U.S. Public, and U.S. Allies and Partners, October 13, 2020.

Blog Post: Scott Kennedy, “Thunder Out of Congress on China,” September 11, 2020.