The Role of Gas in Ukraine’s Energy Future

Photo: Oleksandr Gimanov/AFP/Getty Images

Available Downloads

The Issue

The aim of the bipartisan and international CSIS Ukraine Economic Reconstruction Commission is to produce a policy framework that will help attract private sector investments to support Ukraine’s future economic reconstruction. To support the commission, CSIS will convene a series of working groups to examine a range of issue-specific areas that are critical for reconstructing and modernization of the Ukrainian economy, including in agriculture, energy, and transportation and logistics, as well as addressing the impact of corruption on private sector investment.

Gas plays a critical role in Ukraine’s energy system, and control of the gas industry has been a key fault line of the country’s politics. As Ukraine rebuilds from a brutal war, Kyiv will position its gas resources and infrastructure as a potential asset for Europe’s energy security and energy transition. The gas industry can be a pillar of the postwar economy, but it will be challenging to attract investment for reasons ranging from security risks to regulatory and policy uncertainty. This brief examines the role of natural gas in Ukraine’s energy future. It summarizes Ukraine’s gas resources and the role of gas in the economy, analyzes how natural gas investment fits with other reconstruction priorities, and examines the role of Ukraine’s gas resources in a lower-carbon Europe.

Gas plays a critical role in Ukraine’s energy system, and control of the gas industry has been a key fault line of the country’s politics. As Ukraine rebuilds from a brutal war and seeks to implement long-term goals to diversify its energy sources, there is great uncertainty over the future role of natural gas. On the supply side, Ukraine has substantial domestic gas resources and has managed to keep production relatively steady throughout the war. But state energy companies in Ukraine are coping with difficult operating conditions and threats to facilities, and their future access to capital and partnerships could prove challenging. On the demand side, the role of gas could change substantially in line with the country’s economic recovery. Rapid postwar reconstruction would boost household and industrial demand, but it remains uncertain if policy and regulatory changes will support domestic upstream investment, and Ukraine will have to rely on costly imports from neighbors in Europe.

In a postwar period, Ukraine will gravitate toward the European Union and its energy system. As Ukraine rebuilds and adapts to a new geopolitical reality, achieving energy security will be instrumental to put the country back on its feet, and Ukraine will require assistance from international donors. To facilitate the financing of new energy infrastructure, Kyiv will position its gas resources and infrastructure as a potential asset for Europe’s energy security and energy transition.

This brief examines the role of natural gas in Ukraine’s energy future. It begins with an overview of gas in the country’s energy system and economy. The brief then outlines the importance of natural gas infrastructure among other reconstruction priorities and examines the role of Ukraine’s gas resources and infrastructure in a lower-carbon Europe.

Background on the Natural Gas Sector

The Role of Gas in the Economy

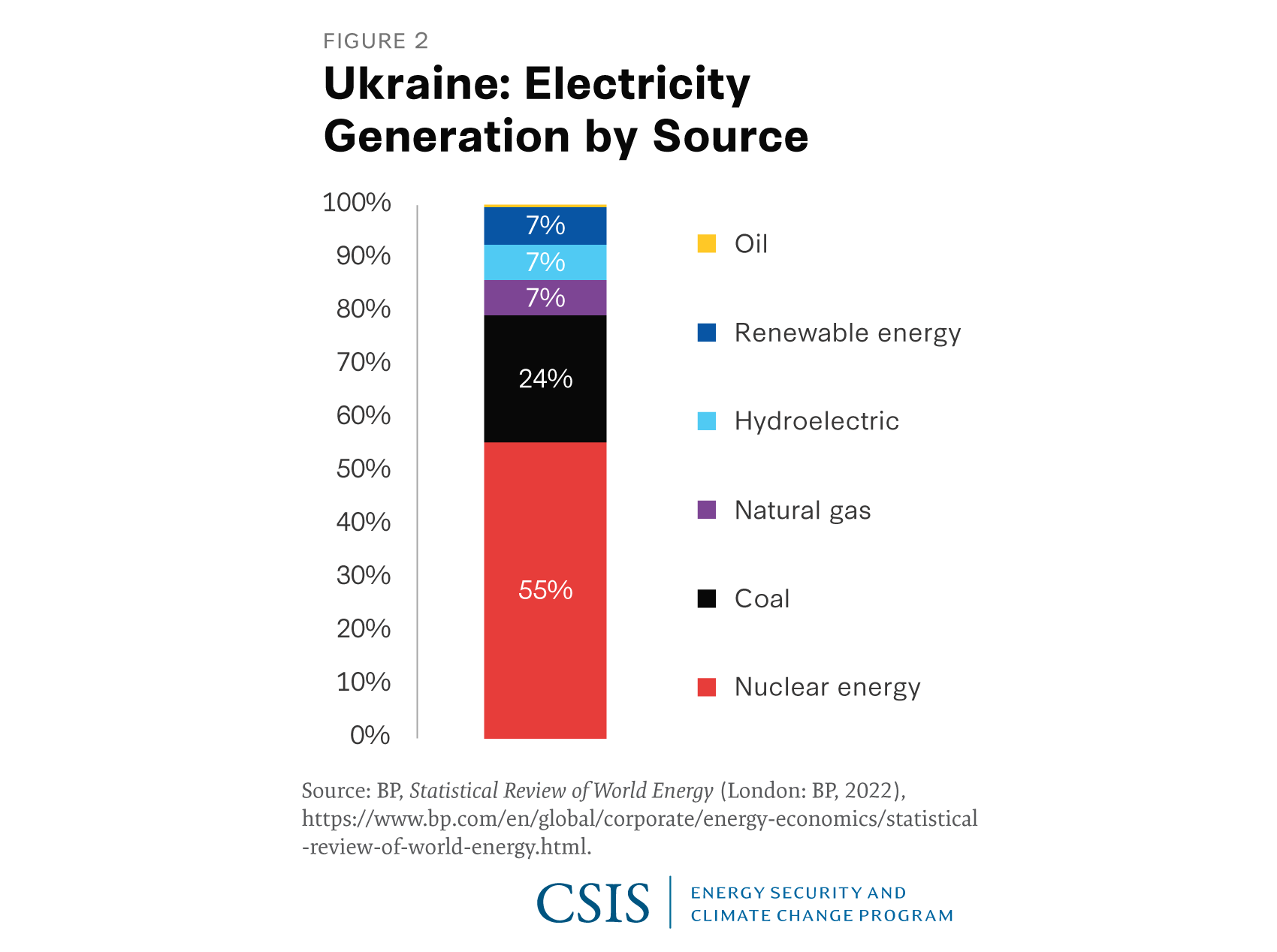

Ukraine has a diverse set of energy sources, with nuclear energy playing a prominent role (see Figure 1). Fossil fuels remain Ukraine’s largest source of primary energy, with coal and natural gas accounting for the largest shares. Due to its substantial hydrocarbon resources and its nuclear energy industry, Ukraine was able to meet about two-thirds of its energy needs through domestic production before Russia began its unprovoked war in February 2022.

Before the war, nuclear energy typically provided more than half of Ukraine’s electricity generation. The generation mix has fluctuated as Ukraine copes with extensive, targeted Russian attacks on its energy infrastructure that have knocked out some 50 percent of the country’s generation capacity. Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant is now offline, with all six of its reactors in shutdown mode, as the facility remains occupied by Russian troops and at risk of shelling and damage.

Renewable energy (including wind, solar, hydro, and biomass) grew from under 2 percent of Ukraine’s generation capacity to around 11 percent by 2020. In 2021, Ukraine set a target to expand the share of renewables to 25 percent of total generation capacity by 2035. Various factors will make it hard to reach these targets, but renewable energy deployment will be a key priority in postwar reconstruction efforts.

Natural gas plays a relatively small role in power generation. Natural gas makes up only 7 percent of Ukraine’s electricity generation, but this share could grow after 2030 to back up intermittent renewable energy and offset the shrinking share of coal generation. Energy efficiency will be a key area of focus postwar to reduce gas consumption in residential use.

By contrast, gas plays a critical role in household and district heating. About 80 percent of Ukrainian households rely on centralized gas supply and more than half use centralized water supplies that are heated by gas. Households, district heating for household and non-household use, and industry account for roughly equal shares of Ukraine’s gas consumption (see Figure 4). This widespread reliance on gas for heating creates vulnerabilities. Attacks on natural gas infrastructure such as pipelines could create a humanitarian risk in the cold winter months.

Domestic Gas Production

Ukraine is one of the largest gas resource holders in Europe, with 38.5 trillion cubic feet (tcf) in proven reserves as of the end of 2020. Its gas reserves, according to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy, grew by an annual average of 3.9 percent between 2009 and 2019, compared with reserve declines in most of Europe. Domestic gas resources have been sufficient to meet about 70 percent of Ukraine’s gas demand in recent years.

Ukraine’s gas resources are concentrated in the eastern Dnieper-Donetsk region, the Carpathian region in the west, and the Black Sea area. Dnieper-Donetsk is home to about 80 percent of Ukraine’s proven natural gas reserves and the region includes the Dnieper-Donetsk and Lublin shale gas basins. Ukraine has considerable shale gas resources. In 2015, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated shale gas resources in the Dnieper-Donetsk region (including dry gas, wet gas, and associated gas) at 76 tcf. The EIA estimates that overall, Ukraine has 128 tcf in unproved technically recoverable shale gas resources. Gas resources in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov area account for just 6 percent of Ukraine’s estimated gas resource base, but Ukraine has lost control of those resources since Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea.

State-owned gas company Naftogaz has historically dominated the domestic gas sector. Since 2016, it has typically accounted for about 70 percent of Ukraine’s gas production. In 2022 its subsidiary UkrGasVydobuvannya produced 13.7 billion cubic meters (bcm), alongside 5 bcm from private companies and 1.1 bcm from Ukrnafta. Naftogaz is Ukraine’s largest company and employs more than 50,000 people. In the first half of 2022, it provided 53.5 billion hryvnia (US$1.8 billion) to the state budget in royalties, income tax, and other taxes—equivalent to 20 percent of the state budget.

The natural gas sector in Ukraine benefits from extensive infrastructure, but the war has placed energy assets at risk. The country’s gas transportation network is one of the most extensive in the world, with 38,600 km (nearly 24,000 miles) of pipelines (transmission and distribution). But sustained attacks on the country’s gas production will impact its ability to remain self-sufficient. Strikes on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure have targeted the electricity transmission grid, leading to increased dependence on gas for power generation. Above-ground gas extraction facilities are more vulnerable to attacks, while 90 percent of gas pipelines are underground.

Gas Transit

Ukraine traditionally served as a key transit route for Russian gas exports to Europe, but over the past decade its gas trade relationships have evolved. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was heavily dependent on Russian gas imports. Its extensive gas infrastructure and status as a gas transit route from Russia to Europe were some of the main strategic assets for the newly independent country. But its sovereignty created an uncomfortable mutual dependence between Ukraine and Russia.

Russian gas supply disruptions to Ukraine in 2006 and 2009 underscored Europe’s vulnerability to Russia’s use of “the energy weapon,” as well as the need for alternative supply routes. These supply disruptions also created incentives for Russia and Ukraine to lessen their reliance on each other. Russia was keen to build new pipelines to alleviate Ukraine’s leverage on its gas exports to Europe, especially the 33 bcm per year Yamal-Europe pipeline. Commercial start-up of the Nord Stream 1 and Turk Stream pipelines greatly reduced Ukraine’s role in Russian gas exports to Europe (see Figure 5). The Nord Stream 2 pipeline (which Gazprom expected to launch in early 2022) would have further reduced Ukraine’s share of Russia-Europe gas transit. Meanwhile, by 2015—one year after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea—Ukraine had secured enough alternative supplies to halt its Russian gas imports. The country now relies on imports from Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland.

Long-standing disputes between Russia and Ukraine over contract terms for gas transit volumes culminated in Ukraine’s 2015 decision to stop importing gas from Russia. The two countries had argued for years over prices, contract length, and the use of take-or-pay contracts. Ukraine’s outstanding debts had climbed as the country rejected price adjustments by Gazprom. Between 2005 and 2020, Ukraine’s gas transit volumes dropped from 136 bcm per year to 42 bcm per year. Today’s transit is governed by the 40 bcm per year deal signed by Russia and Ukraine in December 2019 to cover the 2021–2024 period. However, Ukraine transit volumes reached just 18.7 bcm in 2022.

Gas Import Options to Enhance Energy Security

Ukraine may need to rely more on gas imports from its Western European neighbors this winter and next as Russia targets the country’s critical energy infrastructure. But actual imports will depend on further military activities, levels of domestic gas production, import gas prices, supply availability, and demand destruction due to the war.

Ukraine can secure additional gas volumes from its neighbors, but at a high cost. Last year, Ukraine covered approximately one-third of its 33 bcm gas needs through imports from the rest of Europe; the remainder came from domestic production. Ukraine has a firm import capacity of 54 million cubic meters per day (mcm/d) from Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. These countries will continue to send small volumes of gas to Ukraine throughout the war.

Securing financing for gas imports could become a winter priority. Some gas or liquefied natural gas (LNG) suppliers will not sell gas directly to Ukraine under long-term contracts due to Naftogaz’s credit risk and high political risk. Lenders including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Export-Import Bank of the United States have facilitated Ukraine’s winter gas purchases.

Improvements in the free flow of gas within Europe will bring additional security of supply and optionality to countries like Ukraine. In coming years, Ukraine will be able to buy more re-gasified LNG from Lithuania and Poland (via the newly completed Poland-Lithuania and Poland-Slovakia gas pipelines), Croatia (via Hungary), and Greece (via the Trans-Balkan pipeline). Ukraine will benefit not only from increased LNG cargoes landing in the Baltic states through Poland’s and Lithuania’s existing regasification terminals, but also from the Mediterranean, due to the tightening of energy cooperation in southeast Europe. The “Vertical Corridor” for bi-directional gas flows taking shape in Southern Europe between Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania will also contribute to Ukraine’s security of supply. Hungary even joined this partnership through a recent memorandum of understanding. Ukraine will also import non-Russian pipeline gas, notably from Azerbaijan, thanks to a combination of links including the Interconnector Greece Bulgaria and Trans-Balkan Pipeline.

Despite the vulnerability of Ukraine’s transit volumes from Russia, Europe’s gas infrastructure partnerships are providing new options. Ten years ago, Ukraine began to plan for Black Sea LNG import terminals, despite Turkey’s opposition to any LNG tankers entering the Bosporus, but these plans have since stalled. However, another proposal along these lines resurfaced this year. Turkey’s company Karpowership is also attempting to supply electricity to Ukraine through its LNG-to-power floating power plants, which would be located offshore Romania.

Vulnerabilities This Winter and Beyond

Despite a very difficult winter this year, most households may have sufficient gas to heat their homes. This winter’s gas balance may be less dire due to economic decline (natural gas demand from heating and businesses fell by 40 percent year-on-year from January to December 2022) and abundant storage. Ukraine had approximately 90 terawatt hours (9 bcm) in storage as of December 13. However, many vulnerabilities remain, including the severity of the winter and Russian hostilities that could further damage power plants, transmission lines, and domestic gas production facilities. The call on Ukraine’s thermal generation has increased following Russia’s targeting of the country’s transmission lines, power substations, and transformers. Since October, numerous power transformers have been damaged or destroyed.

Ukraine and Europe remain on high alert for preparing for the winter of 2023–2024 as the continent will need to refill gas inventories this summer with very limited Russian supplies. The International Energy Agency estimates that Ukraine will need to import more from its neighbors, possibly 5 bcm, to refill its storage levels to 14 bcm ahead of the next cold season.

The Role of Gas in Ukraine’s Reconstruction

Ukraine’s energy resources should be a pillar of postwar economic recovery, but the future role of natural gas in Ukraine depends on a few critical uncertainties. Key factors include the status of Russian gas transit, the ability to invest in domestic production and attract foreign investment, and the scale of international financial support to rebuild and redesign Ukraine’s future energy system.

Transit

The future of Russian gas flows to Europe via Ukraine remains a wildcard that will impact Ukraine’s revenue after the war and the sense of usefulness of its large transmission network. There are several possibilities.

First, Russian gas could keep flowing via Ukraine’s gas grid into 2024 and beyond. Ukraine’s current take-or-pay contract for Russian volumes expires in 2024. The parties could continue the transit agreement beyond 2024, providing Ukraine with much-needed income. Ukraine’s transit revenues reached roughly US$2.06 billion in 2020 and were set to amount to US$1.27 billion per year in 2021–2024 following a deal between Gazprom and Naftogaz. However, over the past decade, Russia has worked on bypassing Ukraine with Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2. In the unlikely scenario that one of those pipelines begins to ship gas, the future of Ukraine’s gas transit utilization could be threatened again.

It is also quite possible that Russian gas will stop flowing via Ukraine before or after 2024, and as a result Ukraine’s gas network would be used mainly to transport Ukrainian gas. The pipeline system will then be optimized for the domestic market and regional trade, providing that Ukraine can technically guarantee sufficient pressure in the pipeline in the absence of Russian gas.

Ukraine’s Gas Potential: Reforms Required to Attract Investment

Ukraine is an established natural gas producer with significant resources, but it will be challenging to attract investment for reasons ranging from security risks to regulatory and policy uncertainty. Ukraine’s most prospective areas for conventional and unconventional gas exploration are in the eastern region, including some active conflict zones. And sustaining and increasing production will be difficult without a predictable regulatory framework that can attract foreign investment. To realize its potential, Ukraine will have to resume some of the gas market reforms it initiated in the latter half of the 2010s but abandoned several years ago. This will mean grappling with the dominant role of Naftogaz and the limited space currently available to private investors.

Ukraine began restructuring its gas market in the 2014–15 period, in line with broader economic and political reforms tied to assistance from the International Monetary Fund and the EBRD. In 2015 Ukraine adopted a natural gas market law with reforms aligned to the European Union’s third energy package. This legislation aimed to unbundle Ukraine’s gas system, separating operatorship of the transmission system from upstream supplies. The gas market law also established rules to fully liberalize the gas sector, including gas prices for households and industry, and to allow third-party access to transmission, storage, and distribution. During this period, Naftogaz also established an independent supervisory board, revamped its internal controls, and instituted external audits. In 2017, Ukraine adopted an energy strategy to extend through 2035, including three stages of institutional and policy changes. That document also outlined some ambitious goals for renewable energy, energy efficiency, and integration with Europe. Important changes continued through the end of the decade. In 2019, the National Energy and Utilities Regulatory Commission created new tariffs for transit, storage, and distribution. By the following year, the gas sector was fully unbundled and the Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine fully controlled gas transmission.

There was substantial resistance to these gas market reforms from entrenched interests, and government measures adopted in wartime have rolled back these policies. It is understandable that Ukraine reintroduced price regulation and control of gas distribution to ensure supplies to households. But it remains unclear when Ukraine will revert to the liberalized market structure it briefly enjoyed, especially because natural gas prices remain a politically sensitive matter. The Energy Community Secretariat—an organization joining the European Union with neighboring states to move toward a more cohesive pan-European energy market—suggested in its 2022 implementation report that Ukraine should focus on supporting the most vulnerable gas customers while reinstituting most of its gas market reforms.

Ukraine’s market structure and pricing regime are clearly important concerns for potential investors. If Ukraine hopes to attract more foreign investment for gas exploration and development, important reforms would include new legislation to enhance rule of law and create a stable investment regime. Transparent, predictable policies for exploration and development licenses will also be essential.

Preferences for state rather than private investment in the energy sector could also be a challenge. The energy sector in Ukraine has historically been dominated by the state, and private producers currently produce only about 5 bcm per year. A monopoly over gas transit and extensive control of the gas industry left the fully integrated Naftogaz in a privileged position. In the company’s latest annual report, the Naftogaz chief executive officer states that until recently “the gas transit business made the company look more successful than it really was” and “governance bodies became too complacent over what was essentially parasitic behavior.”

Private companies would prefer to see structural reforms to limit Naftogaz’s control. But to date there is no clear indication that postwar economic reforms will include a renewed effort to create a more level playing field and force Naftogaz into more of a commercial role. Indeed, the rollback of liberalized pricing will likely benefit the state gas company, and it is likely that Ukraine’s government will view state companies as central players in reconstruction and economic development.

A number of regulatory reforms could help Ukraine enhance its appeal to investors. A few action items include:

- Removing the current gas export ban, which will be a key requirement to attract upstream investors.

- Reforming subsidies to prioritize lower tariffs for lower income households.

- Offering a fair gas price to incentivize production. Gas producers need to know they can sell their gas at a fair price, but the Ukrainian domestic gas price is roughly five times lower than EU gas prices, providing little incentive for prospective investors.

- Providing a predictable fiscal framework with royalties reverting to pre-September 2022 levels. The government has temporarily allowed producers to calculate royalties based on the Ukrainian market price rather than using a European hub price. The new formula is based on the highest price among three indicators: Naftogaz’s sale prices; other producers’ sale prices; and the arithmetic average of the Argus Austria VTP price for the next month and this figure on pre-payment terms.

- Addressing corruption and rule of law issues, which will be critical for the Ukrainian economy as a whole but particularly for the energy sector in attracting future investment.

Securing International Financing

The longer the war lasts, the costlier Ukraine’s reconstruction will be. It is difficult to estimate a sum as the war continues, but in September 2022, Ukraine, the European Union, and the World Bank pegged the cost of reconstruction and recovery at US$349 billion. Since the war started, the United States has provided approximately US$32 billion in assistance to Ukraine, including nearly US$200 million in emergency energy sector support and acquisition of critical grid equipment.

So far, the European Union and the United States have remained united in their willingness to assist Ukraine for as long as it takes to win the war and to rebuild the country, but economic recessions will test citizens’ resolve in sharing the burden of the war. It is important to note, however, that the reconstruction of Ukraine will provide new projects and business opportunities for many European companies. In the energy sector, the reconstruction will provide a ground to test new green technologies, such as the injection of biomethane into the grid.

International lenders and donors will influence the rebuilding of Ukraine, and aid could be leveraged to encourage energy sector reforms. As the donor community supports Ukraine, it will be important to focus not just on reconstruction of damaged systems, but on retrofitting and leapfrogging. The European Union, the G7, the EBRD, and other organizations will allocate money to Ukraine’s gas and electricity infrastructure, but this will also be an opportunity to make the country energy-transition ready—perhaps favoring electricity and hydrogen investments over gas. Such support could include “hydrogen ready” infrastructure such as gas and LNG facilities that could conceivably be converted into multi-fuel hubs in the future. The United States and Europe are more likely to invest in the long term if Ukraine prioritizes energy efficiency gains, renewable energy, and clean energy technologies.

Decarbonization and the Role of Ukraine’s Gas to Meet the European Union’s Climate Commitments

Rethinking Ukraine’s Gas Infrastructure to Serve EU Climate Goals

Underground Gas Storage

Ukraine will promote its roughly 10 bcm of unused underground gas storage (UGS) capacity to European governments and traders. This is Europe’s largest storage capacity (excluding Russia): 13 underground gas storage facilities have a total working capacity of 30.9 bcm, and state-owned UkrTransGaz operates 12 of these facilities. Ukraine could begin to store more gas for its neighbors. Moldova already began storing gas in Ukraine last year, and some traders are also taking this storage risk even amid the ongoing war. The U.S. government has provided political risk insurance to some private players to use these facilities and create a hub.

Europeans rediscovered the importance of UGS in 2022, as it provides a buffer between seasonal peaks of demand and supply, as well as a much-needed flexibility in the system to back up the intermittency of renewable energy. The idea that underground storage is no longer needed because spot gas and LNG volumes—reasonably priced—could always respond quickly to demand is no longer in vogue, given the market’s tightness and the precarious picture of Europe’s energy security. The United Kingdom, for example, reopened its Rough UGS facility last year, after Centrica closed the facility due to required repairs that in previous years seemed economically unviable.

It is too early to tell whether Ukraine’s UGS could be used to store other molecules, such as carbon dioxide or hydrogen. Ongoing pilot projects at home and abroad will determine the feasibility and scale of repurposing Ukraine’s infrastructure in a low-carbon economy. The European Union is supporting the UGS Velke Kapusany, a new facility on the Slovakia-Ukraine border, to store the energy from renewable energy sources in the form of hydrogen mixed with natural gas.

Modernizing a Downsized Network

Ukraine’s vast natural gas network, built during Soviet times, is inefficient and over-amortized. As it ages, the pipeline system will require more financial resources for maintenance. Some sections will be decommissioned while others will be modernized or retrofitted. Before the war, Ukraine estimated that modernizing the entire distribution network would require €10 billion for 10 to 15 years, which would include cutting down losses from inefficiencies, methane leakage, and illegal takeoff from industrial and household users. The modernization of the distribution network should be done jointly with the transmission system. Since 2014, the United States and Europe, which have financially assisted the country to improve its energy security, have also gained technical expertise and insights on Ukraine’s requirements.

The goal of repurposing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen and biomethane blending provides an additional argument to keep Ukraine’s gas infrastructure in working condition, modernize it, and rebuild it if necessary to make it “hydrogen ready.”

Hydrogen and Biogas Potential: Hype or Real?

Biogas has gained momentum globally, and Ukraine now plans on producing 0.5 bcm of biogas in 2023 and reaching 8 bcm by 2050. Attaining such rapid growth will require market reforms and EU support. The 2021 biomethane law provided the starting point for the sector as it has allowed injection into the pipeline system. Ukrainian biogas producers are very active given the strength of the country’s agricultural sector, and they plan to switch their activities from biogas to biomethane production this year. Ukraine can get some renewable energy credits by exporting its biomethane to the European Union.

In addition, Ukraine is examining the possibility of repurposing its existing pipeline infrastructure to transport and export hydrogen. There are several ongoing pilot projects focused on blending hydrogen in the country’s distribution network to analyze the impact on material and equipment. In other jurisdictions, it appears that up to 13 percent blending may be possible. Using Ukraine’s existing infrastructure to distribute hydrogen will underscore the need to modernize and replace the grid’s existing gas equipment such as valves, ceiling materials, and gas meters. Europe’s hydrogen infrastructure map suggests that Ukraine will produce hydrogen and that its existing infrastructure will be converted to carry hydrogen. The European Union has also delivered a grant to a Ukrainian company to increase biogas and hydrogen production.

The war will delay some of the projects, which were supposed to be launched in 2022 to 2023, with the aim of redesigning the infrastructure in the 2023–2030 period to establish “hydrogen ready” infrastructure after 2030. There is little clarity on which kind of hydrogen Ukraine will produce (blue hydrogen produced from natural gas with carbon sequestration, green hydrogen from electrolysis using renewable energy, or pink hydrogen using nuclear energy). Europe’s Network Development Plan to 2030 and 2040 mentions one project in its TYNDP 2022 update featuring Ukraine. The Central European Hydrogen Corridor aims to transport hydrogen from promising future areas in Ukraine via Slovakia and the Czech Republic to large demand centers such as Germany and the rest of the European Union. Ultimately, Ukraine’s future as a hydrogen producer depends on sufficient demand from Europe, project economics, and technical capacity.

Conclusion

Ukraine’s gas sector will continue to provide a lifeline after the war to rebuild the country’s industry, bolster energy security, and supply vital revenues for the state. It is in the interest of the European Union and the United States to financially assist the reconstruction and redesign of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Ukraine will most likely remain a transit country for Russian gas, albeit with reduced flows. Ukraine’s gas sector also has the potential to enhance Europe’s energy security with its vast underground gas storage and indigenous gas supply. Depending on market conditions and Ukraine’s supply growth potential, Ukraine has the longer-term potential to become a gas exporter to the European Union.

The country’s gas and electricity networks, now interconnected to the European Union, could eventually facilitate the trading of green and low-carbon gases. Ukraine’s hydrogen and biomethane sectors are nascent but could gain momentum in the coming years. If Ukraine can secure financial support and technical assistance to achieve some of these goals, it could develop an extended life for its pipeline infrastructure.

Ukraine’s natural gas sector can be a pillar of the postwar economy. It plays an essential role today in heating homes and fueling industry, and in the future it could help to back up renewable energy and provide a bridge to hydrogen development. Western donors and lenders can play a pivotal role through vital investments, including in green infrastructure and technology, as well as technical advice and support for transparent, market-oriented regulations.

Ben Cahill is a senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Leslie Palti-Guzman is a senior associate (non-resident) with the CSIS Energy Security and Climate Change Program and the cofounder and CEO of Gas Vista, a market intelligence firm on seaborne commodities.

This project is made possible by support from Invenergy.

CSIS Briefs are produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2023 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.